I had planned to treat you to a well-balanced essay on witchcraft in ancient Mesopotamia. This proved to be a rather big, wide-ranging topic and I don’t think I achieved my goal in a month’s time (+ a day late.)

Still, it’s an irresistible subject, because it overlaps with multiple facets of ancient Mesopotamian history like gender, sociology, linguistics, religion/the occult, law, economics, medicine, etc… choose your own adventure. Well, maybe because I’m a Libra (heh), I can’t choose just one, so I expect I’ll keep reading about it for a while longer and it’s why I couldn’t make this any less shorter (I trust it won’t be read in one sitting, nor should it.)

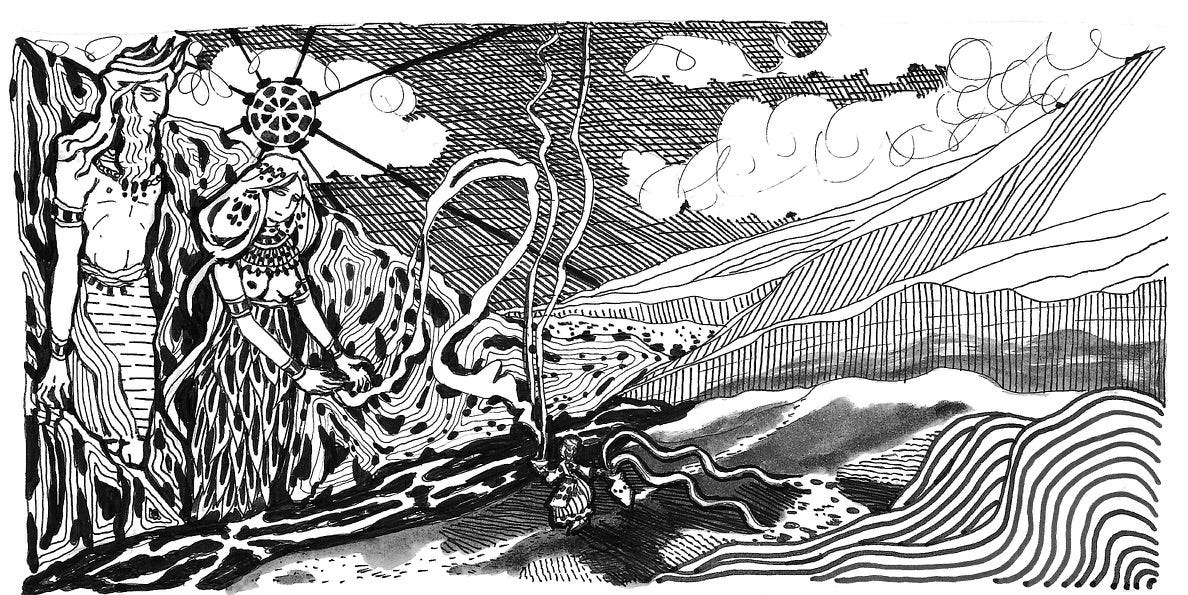

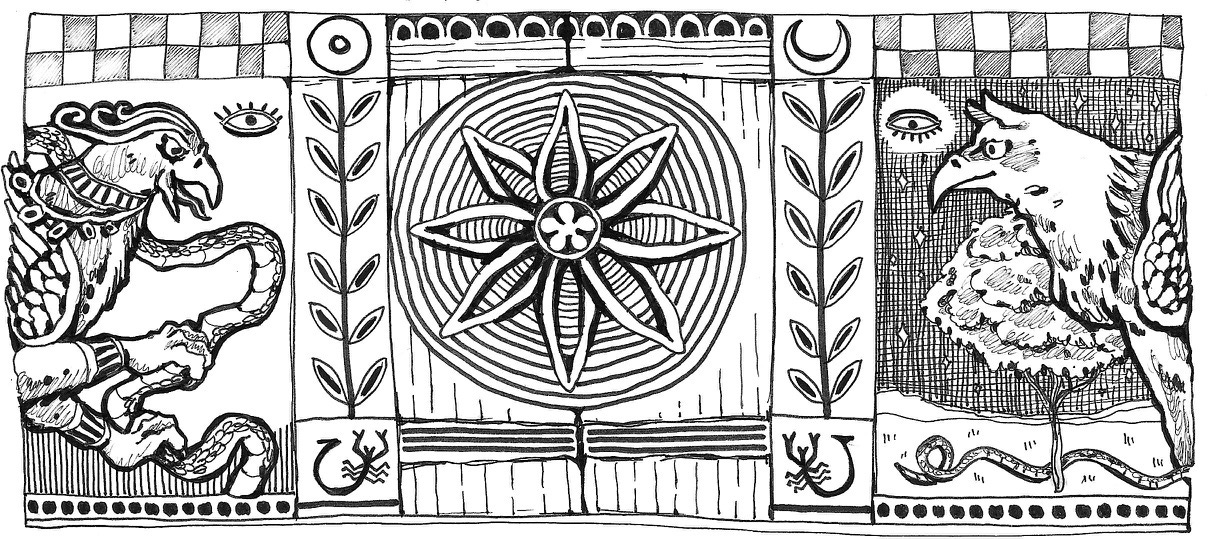

Either way, I come with a sampler tray of fragments, musings, questions and speculation on witches in ancient Mesopotamia (and, some drawings! :D) Though not a full, well-balanced meal, these little bites still have merit. I hope, if nothing else, they spark your curiosity, bring more interest to this wildly interesting topic, and to the history of ancient Mesopotamia more generally.

Ready?

Let’s set the table

Magic was part of ancient Mesopotamian life and religion for (at least!!) 2,500 years. It did not exist outside of religious practice, but was very much an integral part of it. In general: (city-)state-sanctioned magic used for protection, healing, exorcism, and so on, was white magic, yielded by not only, but almost exclusively, male professionals, whose clientele included men & women of the elite; in contrast, black magic was illegal and used for antisocial purposes, as in hexes and curses, and was thought to be the purview of not only, but almost always, female practitioners.

In practice, many unexplained ailments, physical and/or psychological, and even one’s fall from grace in society, if not credited directly to the work of demons (aka the gods’ will) or malicious ghosts, were often attributed to witches.

Who were these witches and why were they so feared and hated? Was it always so? What kinds of evil-doing were witches accused of? How could one prove if someone is a witch or not? How could one go about fighting or undoing witchcraft? Why were women especially vulnerable against witchcraft accusations and were all women equally vulnerable? What does that say about women’s place in ancient Mesopotamian societies, if anything?

Phew. That’s a lot of questions. And in pursuit of answers, there’s a huge and constant hurdle: the historical record is categorically one-sided. All primary sources aka contemporaneous “evidence” about anything related to witches overwhelmingly comes to us from men who perceived witches as evil.

We have zero primary texts by self-identifying or apparent witches, speaking on themselves, their kind, their work, and so on. As we’ll see shortly, considering the popular, legal + religious attitudes towards witches, one would have to be positively suicidal to self-identify as one, or attempt to practice without taking extreme precaution to avoid suspicion, let alone get caught in the act.

There is another thing I came across again and again, and that is that while belief held witches could be either male or female, they are overwhelmingly referred to as female in anti-witchcraft literature, and there’s a curious (and bleak) parallel between women’s status in society (as in their denigration over time) and witches (as in their demonization over time.)

Witches in the prehistoric Village

A toughie. No writing = all we’ve got is archaeology, examples of how later societies did it, and unavoidably, our imagination/best guess.

What can we glean about prehistoric villages in Mesopotamia?

Looking at the Samarra and Early Ubaid cultures, we can say these were rather egalitarian societies, though not perfectly or truly equal. This is because we presume there was a leader - a chief - who represented their respective village ideologically and politically.

Village societies were a mix of sedentary agriculturalists (who also raised livestock like cattle & pigs, fished, but very rarely hunted), and pastoralists, who are almost invisible in the archaeological record, but who concerned themselves with raising sheep and goats and were therefore presumably more nomadic.

Though made up of family units, a sedentary lifestyle likely resulted in (inward) competition between (and maybe within) each kinship group, which already leaves an opening for the hierarchical structures that came later in cities. It’s an interesting mix of subtle contradictions, well-exemplified by the archaeological remains of a Samarra village at Tell es-Sawwan.

There, we observe that each dwelling structure was architecturally recognizable (I should hope so, nothing worse than streets full of houses that look identical haha), nearly all dwelling structures were standardized in terms of size and layout. Each one with a tripartite interior division, made up of a larger middle area (probably communal, with a hearth), flanked by two smaller “wings”, each with essentially symmetrical room divisions (for the extended family members?)

The village even has a cemetery, with rather humble grave goods like small clay figurines and other objects of clay or stone. This and their homes both point to a basically equal society. But, here’s the morbid wrinkle.

At one particular house at the Tell es-Sawwan site, archaeologists found a concentration of child burials (over time.) What made this house “special”?

I guess it’s possible for its location to have been the “x” factor here, but even if that’s the case, I find it entirely believable to imagine the family who occupied this particular home to have had a “pre-eminent” association (real or symbolic) with birth/death in the mind of fellow villagers. Why else would so many of them choose to bury the remains of their deceased child there, instead of beneath their own house floor, or at the shared village cemetery?

As far as grave goods, beads of turquoise, small female figurines of alabaster or marble, and some vases were found at the child burial site. That’s pretty much it.

Maybe it’s a limit of imagination, but I can’t picture a village without some sort of a healer and mystic - perhaps a role sometimes filled by the early witch. Since we have no remains of any studio-size apartments, I’m going to assume she shared a home with her clan. She would have been a woman of special knowledge and power, a person with shamanistic tendencies, magical abilities, and most likely, some actual herbal/medical knowledge as well. Likely, one went to her for both cures & curses.

Later, the ashipu, a male exorcist, magician & healer, would perform just those kinds of duties for fellow-man in the city, and he, we know, considered himself her natural enemy.

The Ashipu in the City

Without writing a whole piece on early Mesopotamian cities, the aspects which concern us in the context of the witch include: the fact that a population of strangers many times the size of a prehistoric village now co-habitated within (and just outside) the city walls; that due to the fact you wouldn’t and couldn’t know all your neighbors, that your extended family couldn’t support your success to the same extent - in other words, that you’re now a small fish in a big pond - you become more sensitive to increasingly hierarchical social structures, and more concerned with your own status within such systems; that, regardless of the specific reasons, women observably go from prominent and visible in society (and religion) to basically second-rate citizen status over time; and finally, that witches were referred to in texts as almost exclusively malicious/evil females.

On that note, let’s look at the ashipu. He was a literate male, a white magician who could deal with a myriad of your problems: everything from pounding headaches, sudden demotions at work (*due to a witch’s curse), and all the way up to pesky ghost hauntings (which may or may not be due to a witch burying a voodoo-esque figurine of you with a corpse - thereby executing an unholy marriage between you and a ghost, tethering it to you and making you sick)... The ashipu was both a magical and healing professional and specialist, who knew both incantations & ritual and legitimate medicinal herbs, salves, and tonics.

One can see how, considering his one foot in the healing realm and the other in the spiritual/magical, and our perceptions of witches as essentially the same, the two could be “pitted” against each other professionally.

It could have ended at professional rivalry, except witches had a bad reputation everywhere. Chicken or the egg, the populace’s fear of witches and state propaganda over time infused seamlessly to categorically demonize witches. The Late Assyrian Empire even held witches in such “high” regard, they believed witches were not only an internal, but also an external threat. As in, they could be blamed for military invasions or failures.

Hell hath no fury like a Witch (in the City)

In terms of psychology, witchcraft became an added way to explain away a medley of illness and misfortune, including a persons’s socio-economic downfall. How? A witch could alienate man from his family, peers or king by falsely inciting the anger of his personal god ( and goddess.) This was essentially the originating patriarch / ancestor of a family line, maybe even represented an amalgamation of previous patriarchs, and was generally an important divine patron of the family.)

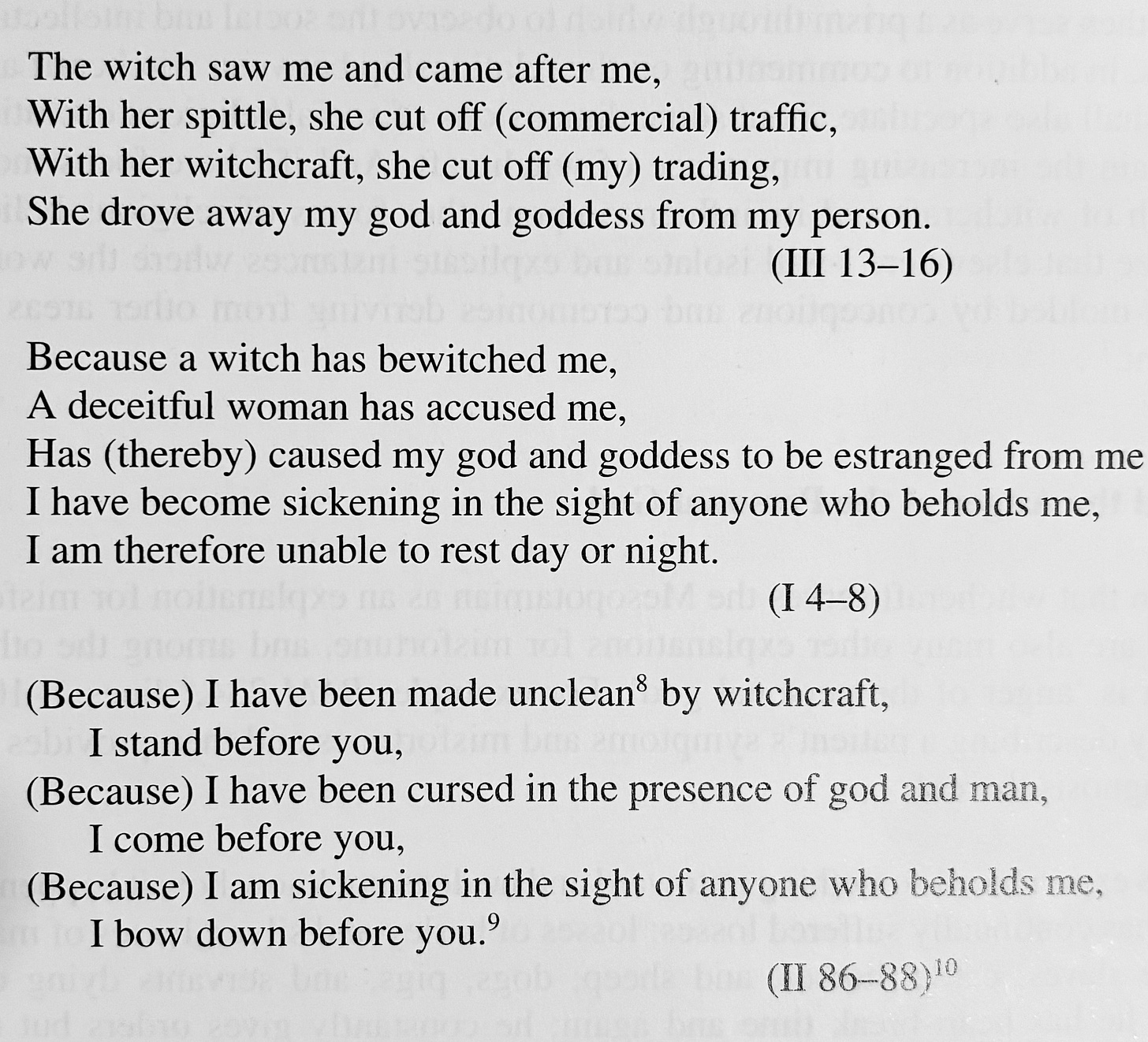

Essentially, through her secret “evil” ways the witch would slander the name of the sufferer, whispering lies in the ear of his personal god. This would cause the personal god to distance himself from the sufferer and the effects of this could extend to a decline in business or socially. As an example, here is an excerpt from the Akkadian anti-witchcraft Maqlu (“Burning”) ritual texts, cited in my copy of this book on Mesopotamian Magic, pg86:

Ironic side-note: the anti-witchcraft rituals overall and thus far deciphered always refer to the bewitched sufferer as male. No doubt, women must have sometimes thought themselves bewitched as well and female clients must have also sought out the ashipu’s expertise, but they too, like witches themselves, are absent in the record. Anyways.

It’s interesting that the belief in the ability of witches to bring about divine anger arose, especially because in this context the sufferer had not committed any sins deserving of his misfortune.

Previously, we understand Mesopotamian ideology to hold that illness and misfortune were caused by divine anger/displeasure/alienation, but always due to personal sin. Now, bad things could also happen due to a witch’s malice, making the sufferer a total victim. As such, you could blame the witch and target suspected witches.

Stepping back out into society, we observe whole classes of female professionals were targeted, denigrated and/or their ability to practice, eliminated, over time. Two things I noticed they tended to have in common is knowledge of healing or magical practices and the ability to move about the city unaccompanied.

In the 3rd millennium BCE, we have records of women holding various professional and public positions, such as healer, scribe, purification priestess, as well as the ability to hold high-ranking titles and to transmit their own personal property. Religion likewise reflected a more gender-balanced view of the world, with goddesses symbolizing and patronizing female-related/perceived activities, and male gods likewise for men.

But, in the 1st and 2nd millennium BCE, we begin to observe some male gods taking over previously goddess-ruled activities (for example, the god Nabu takes over as chief scribeship god over the goddess Nisaba; Enki’s son, Asalluhi becomes chief divine exorcist and purification expert over the goddess Ningirima), or otherwise become “demoted” to more restricted public/private wife and mother roles only.

Likewise, in the real world, the “ideal” woman was increasingly said (by our overwhelmingly male scribes) to be one who satisfied and obeyed her husband, cooked the food, made the clothes, bore children, especially sons, and generally stayed within and managed her household.

That’s obviously impossible for all women, so one alternative route was to become a naditu, or unmarried priestess consecrated to a specific god. Actually, for some time, giving your daughter up to be a consecrated woman even translated to financial savings/benefit to her family, since she wouldn’t marry and her dowry could be passed over to her brothers upon her death. Being a naditu could also mean she could participate in economic transactions (on behalf of her temple) and we have records of some of these women even being scribes (aka literate.) This means access to knowledge, and knowledge is power.

By the end of the 2nd millennium BCE, we’ve got about 60 paragraphs of women-centric law from the Middle Assyrian period and it legitimizes married women as their husband’s possessions, restricts women’s literal movements within the city, and generally places their behavior under scrutiny. Around the same time, veiling begins to be strictly enforced for all women. For example, married women had to wear a veil, while concubines only had to once married, and prostitutes were forbidden from veiling and would be punished if ever caught wearing one.

Slightly earlier, we observe that female professionals in the “healing arts” decline as a whole, while male professionals like the ashipu (and his herbalist-only peer, the asu) are on the rise. If a woman’s place was increasingly inside the home, then any woman outside of it, young or old, was exercising an agency (and public independence) she was increasingly viewed as unfit for. No respectable woman would do such things; only a witch (or I guess, a prostitute) would. Even women caring for pregnant or nursing women were not exempt.

Pregnancy and childbirth were an extremely dangerous proposition for both mother and child, and their domain, practical and magical, was attended to by women only. Male professionals could not penetrate (no pun) this sphere of life and they didn’t like that one bit.

Nu-gig/qadishtu were women of some sort of cultic status, who were not allowed to bear children themselves, but who, alongside midwives, attended to pregnant women. They seem to have been involved in performing magical rituals related to pregnancy and childbirth, and therefore were possessing of female-exclusive magical knowledge. The expertise of the ashipu in this feminine sphere began and ended with him making her a protective amulet, so it’s telling that qadishtu are mentioned in (his) witch lists. The ashipu probably didn’t like being left out and seemed to perceive the “mysterious” knowledge possessed by these female peers of a sort, one that he could never gain access to, as witchcraft and them, as potential witches.

Finally, this may point to a larger theme of viewing women during this time as either good or evil. In a way, any woman like the qadishtu, the midwife, the consecrated woman, and others, was a threat because they didn’t know exactly what she was doing and they weren’t allowed to know. She operated outside of male supervision, could make house-calls unattended, and had (some) power, by virtue of her exclusive knowledge - just like the witch was imagined to. Add to this women’s general perception as prone to impurity, and it makes a little more sense. For example, during menstruation, a woman likely had to sleep (with other menstruating females of the household) in a designated room at the periphery of of her home and away from her husband and the all-important central room, with its hearth and coincidentally, the place where the family’s personal god (and goddess) were thought to reside. Likewise, mother, child, and the women who attended them during childbirth, were perceived to be “unclean” and “surrounded by dangerous powers.” Sigh.

So then, this brings up the question, how did one deal with suspected witches?

Witches on trial: the dreaded divine River Ordeal

The following true account comes from the reign of Zimri-Lim, a 2nd millennium BCE king of Mari (present day Syria), and a contemporary of the famous Old Babylonian Empire king, Hammurabi:

A young girl, Marat-Ishtar, is accused of having bewitched a young boy, Hammi-Epuh. The boy’s father, Dadiya, tells the authorities that the wood young Marat-Ishtar had given his son, the same wood later used to prepare the boy’s meal, was bewitched. Inside it, an alleged evil spirit lay in wait. Once released by burning flames, the evil spirit leapt out to poison the food being prepared over the fire that freed it. Perhaps it also poisoned the bread and beer around it. Either way, Hammi-Epuh ate the food, the bread, and drank the beer - and then, he fell ill.

Dadiya doesn’t just want justice for his son, he wishes to free him of the evil spirit, and the way to do so is to destroy the responsible witch. The law obliges him with the special provision designed to deal with just these types of murky allegations: young Marat-Ishtar - or a substitute(s) - must go through a divine River Ordeal.

River Ordeal. You can probably already guess what it is just from the sound of it. Starting in the Old Babylonian Period, River Ordeals were the way to solve legal disputes that were otherwise impossible to - by rational means anyway. For example:

When you can’t prove your wife is cheating. Yes, it would be she who would be overwhelmingly likely to be accused of cheating and then put through Ordeal. For although I’m positive both spouses cheated on each other then just as they still do today, the husband could legally (1) have more than one wife, (2) have a concubine, and/or (3) enjoy prostitutes, without ever raising a brow. So, husbands would seemingly have very little reason to pursue hidden extramarital affairs, when they could so easily get extra sex and extramarital sex out in the open. But, crucially, wives could legally lose their life (and property) over the mere accusation of having an extramarital affair (by the way, if she did have a lover and was actually caught in the act (aka there was evidence and no need for Ordeal), then the other man would likewise lose his life.) (And, no, wives could not legally have more than one husband or enjoy prostitutes.)

When you can’t prove that somebody is a political traitor. Even the most potentially powerful female around, the queen, was not safe from such allegations. In fact, we know of a nameless queen of Zalmaqqum, a wife of king Yarkab-Addu of north-west Mesopotamia, who was hit with the ultimate (and deadliest) trifecta of accusations one could legally levy against a woman, be she the queen or not: (1) that she was a witch, (2) that she had committed treason, and (3) (that ole classic) that she had “open(ed) her thighs” for another man. Someone in that kingdom well and truly wanted this queen dead and gone for good - the reason why, and the details of her Ordeal, are lost to history.

And of course, you resort to this when you can’t otherwise prove that somebody is a witch

In these types of cases, where sufficient evidence was absent from either accuser or accused, the law looked to the gods - here, the river god - to rule on its merits. An accused party was compelled to dive to the bottom of the river, and/or perform other dangerous feats in its waters. The river god would then decide their guilt/innocence. Us mere mortals would understand the river god’s verdict based on whether the accused came back up alive or not. If they did, the accuser automatically loses their life and their property goes to the surviving innocent party. And, if the accused drowned - the vindicated accuser would take possession of the guilty, and now deceased, party’s assets.

The Ordeal was both ritual and trial. It unfolded over a night and a day, whereby the accused, the accuser, the authorities (and plenty of onlookers, I’m sure) go to (a specific part of) a river. The first night is a serious religious affair, replete with ceremony, several literal and cultic cleansings, offerings and prayer. The next day, the trial itself is held, and one way or another, someone is going to lose their life and their property.

Back to our alleged young witch. Marat-Ishtar has a mother, Meptum, who must have loved her daughter, for Meptum invokes substitution and takes Marat-Ishtar’s place as the accused undergoing Ordeal. Before diving into the water, Meptum swears an oath (a solemn act) of Marat-Ishtar’s innocence - her daughter did not cast spells over the firewood given to Hammi-Epuh, nor over his bread, food, beer, nor bewitch anything else.

We don’t know Meptum’s age or occupation, or anything at all about her general state of physical health or swimming ability - but we do know she did not make it. Meptum “married” the river god - a striking euphemism for drowning.

When I first read this story, it broke my heart. I don’t doubt for a second that Dadiya knew full well the repercussions triggered by a witchcraft accusation (i.e. Ordeal.) He may have even expected Meptum to step in her daughter’s place. This principle of substitution I keep referring to functioned in other spheres of Mesopotamian religion and society (I’ll probably write on it in more detail at a future date), and it was nothing unusual in the context of River Ordeals either.

So, was Meptum the “target”, rather than her young daughter? Without knowing her trade, we can’t guess. It seems notable to me that it was she who subbed in for Marat-Ishtar, rather than an able male relative or even a slave - which makes me wonder if they had any; which then makes me wonder if they themselves were socially inferior to the Dadiya household.

What happened to young Marat-Ishtar after this? Was she orphaned and taken in by some temple priestess, to be raised in exchange for labor? Or, seeing as the river god had ruled against her claim of innocence, her mother dead and her own reputation presumably sullied as a “convicted” witch, was she banished from the city? We have no clue.

The end, at last

Phew, we made it to the end. This was actually a drop in the bucket, and a topic I’ll probably/inevitably explore again in the future. For now, I can write no more. Til next time!

Necessary Disclaimer:

Please do not be tempted to quote me - check out what the experts aka my sources said, all and always listed at the end of these types of dispatches. Any hyperlinked names or phrases above and throughout are a courtesy to you to save you the googling. They were not necessarily used as reference material in the writing of.

I am not an Art Historian, an Assyriologist, or a Historian. I have a BA in Cultural Anthropology (cool, but unrelated), a lifetime of insatiable curiosity and reading of history books (+ open-source scholarly articles heh) on a variety of historical periods. Of course, I carry with me my limited understandings, interpretations, biases and opinions as I go on my little self-study treks. In short, I love learning about ancient history, but I am NOT an expert.

Sources:

Witchcraft Literature in Mesopotamia (2012) by Tzvi Abusch

Mesopotamian Magic: Textual, Historical, and Interpretive Perspectives (1999) by Tzvi Abusch and Karen van dear Toorn, editors

Everyday Life in Ancient Mesopotamia (1992) by Jean Bottéro

This was so interesting… please post more; I love reading your work ❤️

Yay!! Another Mesopotamia-person 😍 Helloooooooooooooooo

(Being an Assyriologist I'm gonna be the looming shadow fact checking everything on this account from now on eheheheh..... just kidding meeting another Mesopotamia-nerd always feels like meeting another Dane out in the world, cause, you know, there's practically none of us so it's always special teehee)

And really nice piece! It takes patience trying to even remotely immerse oneself in the confusing maze of Mesopotamian magic and witchcraft, and which of the many kinds of exorcist-doctor-priest does what, and so on, so really, cudos!